WATCHING WEATHER

Elephant Hill Test Plot

Interview with Joey Farewell by Jen Toy

DATE: October 16 2023

Jen: I wanted to create this post to share information with our Test Plot community about the wondrous topic of weather. Watching weather patterns and climate forecasting is both an art and science. It’s also increasingly necessary for the business we’re in, and a field that I want more people to understand given the weather extremes we’re all living through nowadays. To that end, please enjoy this conversation with Joey Farewell, a resident of El Sereno, conservation co-chair of Los Angeles CNPS, and unofficial Test Plot meteorologist.

PS. easy access to the links that Joey mentions:

WeatherWest Blog (check out the comments)

Tropial Tidbits (access to GFS model)

National Weather Service

Ambient Home Weather Station

Weather Underground (crowd sourced data from home stations)

Elephant Hill Test Plot

Interview with Joey Farewell by Jen Toy

DATE: October 16 2023

Jen: I wanted to create this post to share information with our Test Plot community about the wondrous topic of weather. Watching weather patterns and climate forecasting is both an art and science. It’s also increasingly necessary for the business we’re in, and a field that I want more people to understand given the weather extremes we’re all living through nowadays. To that end, please enjoy this conversation with Joey Farewell, a resident of El Sereno, conservation co-chair of Los Angeles CNPS, and unofficial Test Plot meteorologist.

PS. easy access to the links that Joey mentions:

WeatherWest Blog (check out the comments)

Tropial Tidbits (access to GFS model)

National Weather Service

Ambient Home Weather Station

Weather Underground (crowd sourced data from home stations)

Jen: Hey Joey, welcome and thanks for chatting today. How did you get interested in following weather?

Joey: Hi Jen! I’ve always really enjoyed the weather and its nexus with many of my favorite interests –– chasing powder for skiing & snowboarding, growing native plants, and learning about Californian habitat. I also grew up with a father who’s totally obsessed with weather, so meteorology was (and still is) my way to connect with him. Nothing gets my dad more fired up than a big snow cycle forecast for 5-7 days out in the Sierra Nevada –– and it’s really fun to share that excitement.

Also I’m a trusts & probate lawyer, and while I really enjoy estate planning work, meteorology makes for a fun side hobby.

Jen: I’ve heard you talk about how following weather makes you feel good...can you share about that more?

Joey: Yea, accurate forecasting is kind of like having a superpower for the stuff I’m into. You ski better snow (because others foolishly made plans without following the data –– leaving more tracks of deep powder), you plant native plants at better moments (see: our impeccably timed Elephant Hill Test Plot installation, which was followed by 3” of rain just a day later, and our relaxed watering schedule), and you are just generally more connected with the natural world around you. Rain isn’t something that just happens to you that day; instead, you observed a process, maybe learned something along the way, and then perceive the phenomenon of water falling from the sky. It also gives one an illusory feeling of control in an otherwise indomitable universe. So that’s cool too.

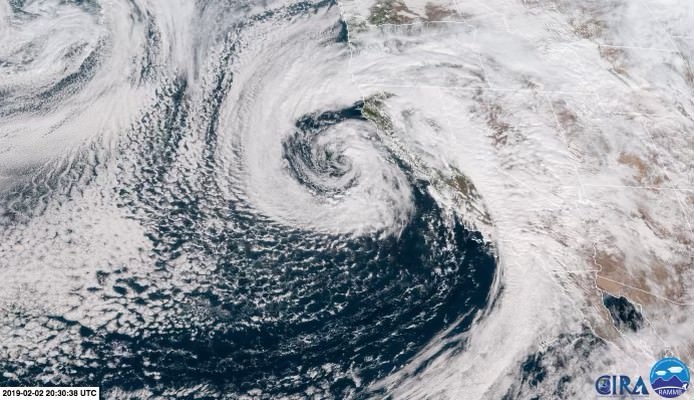

Jen: Weather is kind of interesting because it connects global patterns with local experience. How do you think about scale when you are following weather trends?

Joey: That’s an interesting question. I would say that, when it comes to precipitation and snow in California, the storm door is (as we well know) closed more often than it’s open. Global patterns often conspire against us here, particularly in Southern California –– and that seems even more true in an era of climate change and “stuck” weather patterns. When that storm really opens, though, it’s both (generally) great for us and really problematic for other places that are far more accustomed to receiving rain and snow. Big precipitation years in California usually indicate some level of drought in the Pacific Northwest, fires in Australia (particularly during El Niño years), and below-average snow on the East Coast. When we’re scoring, the world often isn’t. That translates to forecasting, too –– when we see big high pressure building in the Hudson Bay region, for example, we can usually assume that the Northeast will get shut out and we can expect stormy low pressure out west. And when we see a pattern favoring cold temperatures and snow in New York, it’s usually time to put away the skis and break out the hose in the garden.

Jen: What is your favorite forecasting model? What is it useful for, and what are the limits?

Joey: Let’s put it this way –– all models are wrong, but taken in context, and in sum, they’re useful. Supercomputing, the internet, model aggregator websites such as Tropical Tidbits, weather blogs like WeatherWest, they all have made for what I consider the golden-age of home forecasting, but with that comes a myriad of ways to misuse that data and get humiliated in front of your friends and colleagues.

So here’s what I do. I generally use the USA-based GFS, not because it’s the best (that would be the ECMWF, the European model and gold-standard for forecasting) or because I’m particularly patriotic (our tax dollars at work, though!), but because it’s freely available, it’s generally pretty good out to 7 days, can spot things with some accuracy out to 10 days, and after that is, to put it kindly, useless. We call the post-12’ish day forecast “fantasyland” in model data, because it’s just too hard at the moment to forecast that far in advance with (1) our computing limits and (2) the inherent chaos of weather. It also “runs” (produces readable data) 4x a day, whereas the ECMWF only runs 2x a day (viewable around noon and then midnight), so the latter isn’t quite as good for a daily weather nerd routine.

For big cycles and events, it’s best to use multiple models –– so that’s when we are looking at the GFS, the ECMWF, and other models like the German IKON and Canadian CMC, all to try to find a consistent solution between them to best anticipate what is really going to happen. And then there are also short term models, like the NAM and HWRF, which are run at higher resolutions and can spot things (like isolated thunderstorm development or rain shadowing –– which is when topographical features such as mountains “catch” the moisture from rain-bearing clouds and deny it to the areas behind them –– where certain areas might get skunked) that the lower resolution models can’t. There’s also the ensemble models, which is when the GFS, the ECMWF, and others, are run multiple times and then averaged together in a super-model of sorts –– but that data is more available to the pros than the lay forecaster.

And what’s critical is to corroborate model findings with other users, too. The internet makes this more possible than ever (though I’ve got to shout-out a few weather nerds of mine in real life, where “lol dude the 18Z GFS is totally bonkers” is a real thing that we text each other), where we can connect with other model-riders (yes, that’s a real thing) on fabulous online weather forums like WeatherWest. On the comment board for each post (follow the activity on the most recent post for up-to-date analysis), you’ll find general chatter about current conditions, model data, storm prognostications (and post-mortems), banter, and –– my personal favorite –– the absolute hazing of folks who call “bust” on a storm far too early, before any meaningful precipitation or effects were forecasted to begin in the first place. These folks aren’t professionals, but they’re close. And oftentimes these users are the first to spot long-range patterns and atmospheric perturbations that result in that thing we all love: storms.

And speaking of pros –– I’ve absolutely got to mention that the National Weather Service is an invaluable resource for both confirming your own read of the data, but also illuminating many other things you will invariably miss in your forecasting. They present their accessible info through social media, but the good stuff is in their AFDs –– called “Area Forecast Discussions.” These discussions (updated 2 to 3 times daily) contain thorough, high-level analysis of both short and medium term forecast windows. They usually don’t go out past that time-frame (see the above community WeatherWest for proper fantasyland chatter) but are seriously invaluable for learning to understand this stuff. And again, National Weather Products reflect our tax dollars at work! In a world of complicated, slow government –– I love reading and learning from the professionals at the National Weather Service. It’s public work at its best.

Jen: What kind of weather station do you have at your house?

Joey: Ambient Weather station. You could pay more for a Davis, etc, but these work great, are user-friendly, and connect well with Weather Underground and a range of data supporting apps.

Jen: Couple more questions. You’ve said that this has been “the best year ever” for habitat restoration plantings –– can you tell us why that is?

Joey: Oh man, the 2022-2023 planting year! Wet season for the ages. Deserving of a treasure trove of superlatives (I’ve written too much already –– so I’ll spare you). We had a strong storm in early November (2-3”), a couple smaller fronts that kept things moist and happy through early December –– at which point a series of atmospheric rivers took aim at California and just unloaded consistent, cold storms through late March, early April. We had one “long” break from precipitation, like 12 days in late January and early Feb, and then it was game on again. Then, as if all that rain wasn’t enough (but at 38” in El Sereno, it definitely was), May was downright cold and cloudy, June went full gloom, July wasn’t that bad, and in August –– it rained like (almost) never before during a SoCal summer! 4” in El Sereno (bringing our season total up to 42” incredible inches for the wet season ending September 30), 6” in Glendale, just all totally bonkers. After all that, the weather gods delivered perhaps the most unexpected coup-de-grace: September was nice and cool for once! I think we watered the Elephant Hill Test Plot like 6 times all year. Unbelievable.

Jen: Finally, any thoughts on this coming year and the predicted El Niño?

Joey: I’ve got a few thoughts! More likely than not that we get above-average precipitation in SoCal –– which is a big deal in California, where we are more likely to have a dry year than a wet one –– as strong El Niños are as sure a bet as you’ll find for wet season forecasting. In fact, it’s really only strong Niños that move the needle in that regard for CA, and we certainly can get wet years without them (last year was a La Niña).

Indeed, on one hand, things look good. A strong El Niño (particularly an east-based one, as we have now) should theoretically amplify the southerly jet stream into Southern and Central California, propping the storm door open for mid-latitude cyclones to provide the ultra rare back-to-back wet years for LA.

But in an era of climate change and rapidly warming oceans, things seem less predictable than usual. Because El Niños operate via an oceanic-atmospheric relationship that relies fundamentally on ocean temperature anomalies –– in layperson terms, a bunch of warm water in a certain place (certain zones of the equatorial Pacific) that are markedly warmer than areas around them –– they may be less impactful when the entire Northern Pacific is basically on fire. The temperature gradient might be there for strong Niño effects (ie, a strong southern jet stream), but what if the overall oceanic temperatures in the mid and northern latitudes are warm enough to disturb that effect? That’s what some folks smarter than me think happened in 2015-2016, the last strong El Niño (which, outside of a riveting week in early January, was a total bust for SoCal storms).

So yeah! Looks good, but I wouldn’t be surprised if we go dry, perhaps owing to the extraordinary warmth above, or for another fly in the ointment yet to be discovered. But that’s part of the fun, isn’t it?

(OK well, not the global warming thing)

Jen: Thank you for sharing your knowledge with our Test Plot community. Next time, let’s talk more about local weather and microclimates.