RAINY DAYS AND RECOVERY

Rainbow Canyon Test Plot

By Andre Grospe

Test Plot Landscape Designer

Date: Jan 15 2026

Rainbow Canyon Test Plot

By Andre Grospe

Test Plot Landscape Designer

Date: Jan 15 2026

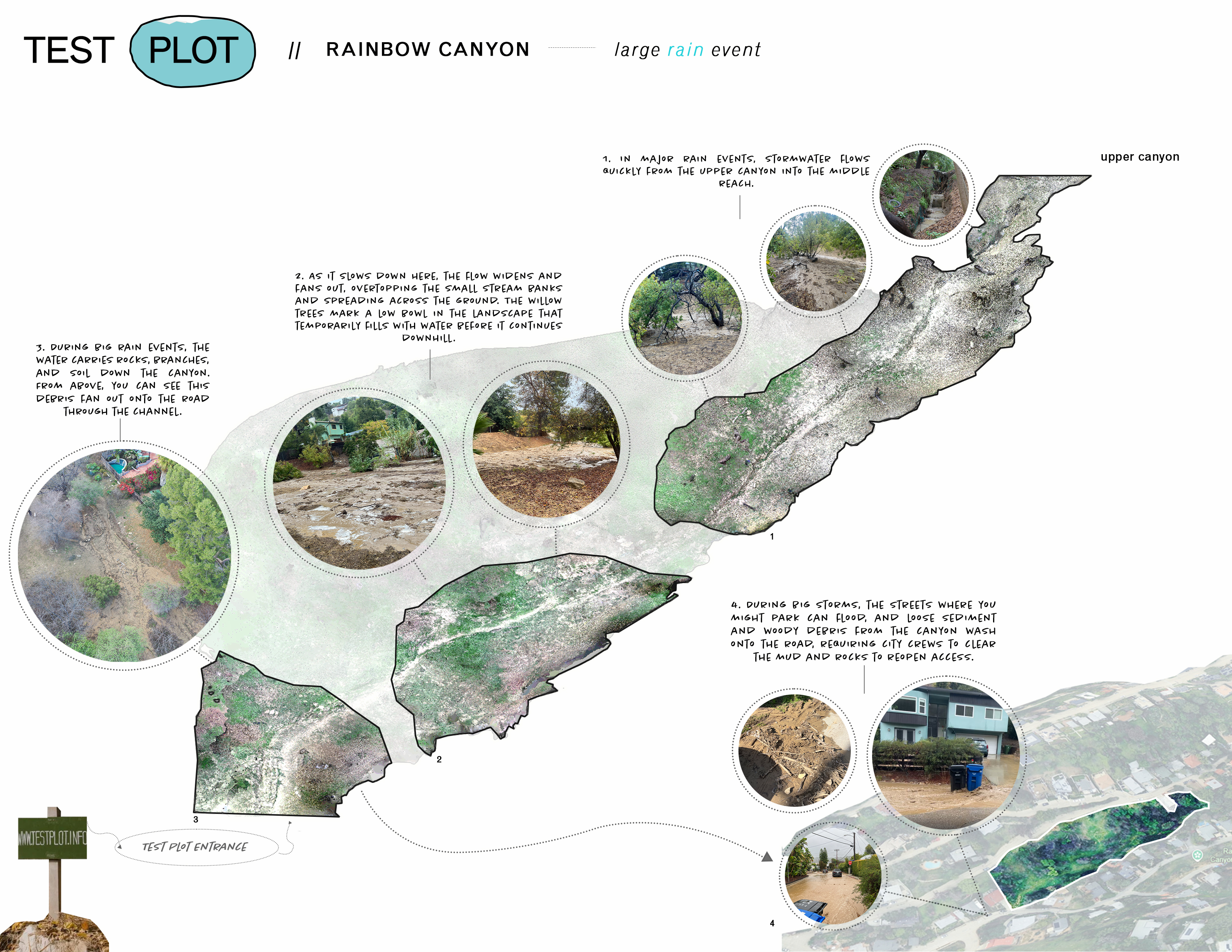

If you returned to Rainbow Canyon after these winter storms you may have noticed some changes. There are several new washes of sand, new patches of litter and debris, extra ruts in the ground, traces that something powerful came through. It can feel like forensics, seeing what’s left after a big rain and deducing what might have caused these changes. They are subtle reminders of how dynamic Rainbow Canyon can be.

Obviously this is not a unique event and heavy rains can be more a nuisance and hazard than a wondrous experience, especially to those living downstream. Previous documentation clearly shows more severe debris flows than I had seen. But these gentle and moderate rains gave me a chance to document and appreciate the nuances of a stream and what they offered to the overall experience of the lower canyon (as opposed to just focusing on the awesome and terrifying high flow events). What kind of aesthetic experiences do we gain if we implemented best management practices (BMPs) and other channel modifications?

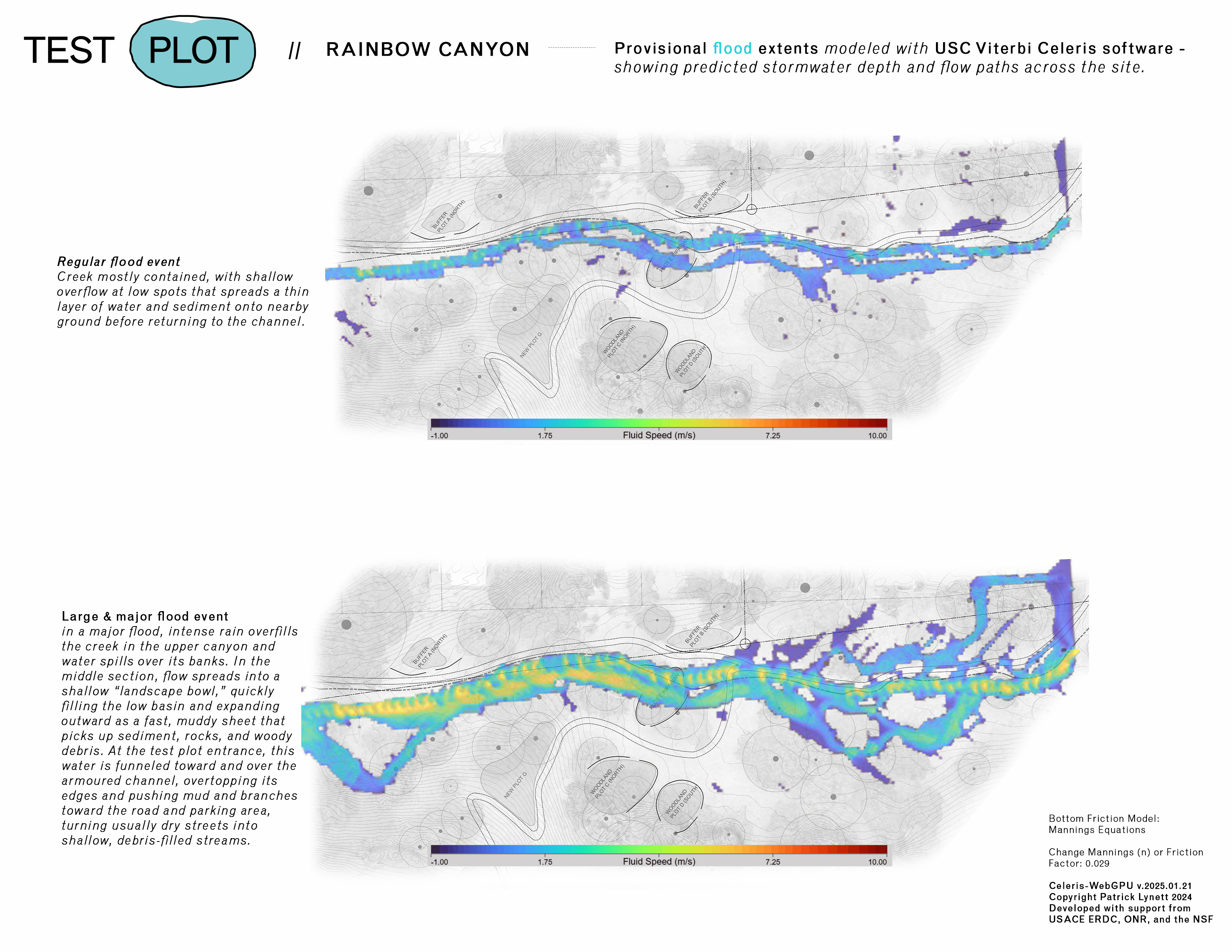

I would suspect that most who wander in and out of Rainbow Canyon see its heavily eroded channel as an ugly scar, an obstacle to jump across, or a problem to be solved. While it is these things, it is also the product and home of an ephemeral stream that has shaped the way we design and work with the lower canyon plots.1 The entrance trails into the lower canyon are defined and continually eroded by stream diversions and have stymied and frustrated our mulch truck drivers and resulted in more than one twisted ankle. During heavy rain events sediment, logs, and other debris wash out directly onto Ave 45. Suffice it to say, this stream is a blessing and a curse and currently, with the help of a grant from the Water Foundation and Rose Foundation, we have been trying to understand and mitigate these problems. These storms have been an amazing opportunity to rigorously document these stream dynamics, testing out new methods and technologies along the way.

During the November 15th rain event, we ended up getting 1.65” of rain.2 When I arrived to document, the canyon wasn’t the raging river I had expected, with no water actively running through the channel. Not too long after I had arrived however, I heard a light gurgling sound and saw the fresh grasses growing in the channel begin to fold over. The smell of fresh soil filled the air. Excitedly, I was able to capture the first flush through the canyon. The water was a dark, opaque brown (think hot chocolate) but was relatively relaxed, tumbling over the roots and rocks. I followed the water out to the entrance and watched it pour over the stone steps you pass when you enter the canyon, creating a lovely set of waterfalls before emptying out onto the street.

Elsewhere in the site, small springs and pipes burbled out water. I wondered if these were some of the bits of infrastructure we had found digging through city datasets or just gopher holes being flushed out. Either way, they were cute curiosities closer to the entrance of the canyon.

I left before the rains got heavy, but when I returned the following week, more changes than I had witnessed had obviously occurred. Over the course of the storm, water had carved a third diversion whose path left a trail of bent grass and new sand. This was a particularly useful and reassuring confirmation of our numerical modelling, which, while rough, had similar flow patterns during lower and higher flow events.

The water had also left an array of beautifully complex depositional forms, some sinuous and fan-like, showing where water crossed and flowed around different obstacles. Others were soft, dramatic, pillowy ripples, particularly in the stone steps at the entrance, where the waterfalls created stirring eddies that caused sediment to slowly accrete in the pool. Some parts of the channel seemed to fill up with sand.

The next rain event of 2025, on Christmas Eve, was a much larger one, almost 2.6 inches in the area. Following the LA County Hydrology Manual, that would make this an almost exact 2-year rain event in the Mount Washington area.3

With November’s fieldwork in the back of my mind, I returned with a better camera (a mistake) and a focus to try to capture the nuances of the flow. I had a goal to connect the flow of water to some of the depositional forms I saw in November. I also wanted to try a new monitoring technique, using an iPad’s lidar scanner and Polycam to stitch together a plan of the flow path which worked well even despite some of the tall grass and standing waves confusing the software a bit.

Christmas Eve’s storms were intense and unpredictable. The channel was nearly full to the brim with water whipping around rocks and logs. The stone steps at the entrance were overflowing, spilling out onto either side of its walls. Large flashes of water came in pulses, signaled first by sound, then by color as the stream darkened with new sediment.

When I returned after the storms, on our first workday of 2026, the canyon had again been noticeably rearranged. A tire lodged itself in front of the riparian plot, causing an extreme buildup of sediment, creating a new sand bridge to cross the channel. But the tire had also diverted water onto the trail between the riparian and fire buffer plots, further degrading it.

Upstream of the riparian plot, the channel continued to transform into a gulley with a defined headcut that continues to erode and deepen the channel. Left unchecked, this section will continue to deepen and retreat upstream.

Further downstream past the riparian plot was a new deposit of sand. Logs and debris seemed to have blocked the typical flow path, redirecting the water further away from the trails. Formerly this tributary would only flow during higher storm events, but with the current debris blocking the way this could be the start of a new flow direction. It will be something to keep an eye on during the next rains. How will water interact with this loose material? It will be an unpredictable and exciting experiment. Will we remove the newfound debris or leave it in place to train a new flow path? To be determined.

In the meantime, volunteers at the 1/10 event, mostly returning visitors, got right back to work mulching and weeding the switchback plots. Alex and Isaac installed logs and drainage to reinforce the switchbacks. Alex sprinkled wildflower seed in trail spoil. The elderberries are sprouting new leaves and flowers are beginning to bloom. I look forward to tracking their progress through the spring. After our work session finished, a family came down to the new sand wash and started to make sand castles. The next few sessions will focus on recovering and repairing from these storms and preparing for the next, whether they be next month or next year.

Storm flows in Rainbow Canyon are no joke with flash floods being fast, unpredictable, and dangerous. But in a moderate rain event canyons like Rainbow Canyon activate in surprising ways. I hope some of you get a chance to swing through and maybe even linger (the dense branches of the elderberry and palm tree make good site umbrellas). Open spaces like these give us Angelinos a way to observe rain and flowing water in a different way, not just rushing past curbs and concrete lined channels, but as dynamic natural features that continue to alter the landscape. Fingers crossed for more rains in 2026. When they come you know where I will be!

1 From the EPA, “An ephemeral stream has flowing water only during, and for a short duration after, precipitation events in a typical year. Ephemeral stream beds are located above the water table year-round. Groundwater is not a source of water for the stream. Runoff from rainfall is the primary source of water for stream flow.” This is opposed to an intermittent stream which relies on groundwater and is only supplemented by rain. The more you know! https://www.epa.gov/sites/default/files/2016-02/documents/realestate_glossary.pdf

2 https://www.weather.gov/wrh/climate?wfo=lox

3 https://www.arcgis.com/apps/PublicInformation/index.html?appid=cd5ec68b636f4e47bbba5b8e9307be1e

https://lacreekfreak.wordpress.com/2010/12/22/how-to-figure-out-a-fifty-year-storm-and-other-storms-too/

5 MONTHS WITH TEST PLOT

By Kaitlyn Ray

Cal Poly SLO landscape architecture intern

DATE: Dec 01 2025

ON ART + CARE....

There is art in stewardship, in smallness, in care, in recognizing how that art becomes inscribed on a place. In short, this is what I saw at Test Plot: art inscribed upon a landscape as a result of many hands who care about their common home and about each other. The soul in the land’s caretakers, the sweetness in their interactions, and the buzzing life that springs forth from it all. These, surely, are all metrics of an artful place.

Interventions need not be immediately impressive or very large to make a difference. Small, piecemeal interventions done with Great Care mean infinitely more in the scheme of social landscapes to be loved rather than simply admired. Such interventions reach success on account of their radical outpourings of care: investment in a place paired with a desire for it to be excellent. The land needs people who care about it, listen to it, and who can form a kinship with it. This idea of small kinship is actually very big and very meaningful; this, I have understood more than ever during these last five months at Test Plot.

ON A PRACTICAL NOTE....

I became intimately familiar with the plants on our plots, refining my understanding of their character beyond identification. I was involved in cataloging and mapping existing plants, setting up iNaturalist profiles, designing ethnobotanical plant tags, and creating a huge Test Plot plant list with useful attributes for stewards. These, among other tasks, allowed me to better understand the nuance and character of ecological interconnectedness, as well as where people + care fit into it all.

This interconnectedness, the relationality of plants with humans, with each other, and with the rest of the environment, became most evident during the plant list creation. Plant-human relationships revealed themselves through a study of naming, propagation, care, and ethnobotany. A study of plant communities, ecosystems, and reproduction became a lesson in plants’ relationships with each other. A late addition, what species the plant hosts, revealed how specific plants and animals interact with and rely upon each other. Each, in some way, informed the way I see how environmental relationships develop and sustain themselves. Plant-human, plant-plant, and plant-environment: each an ecotone, representative of immense richness and diversity that can only be found in their intersections.

Understanding this made the work of land restoration so much richer; rather than simply knowing and designing for the end result, I can know and design for the interconnectedness + relationality that precedes and produces that result. It is a necessary step back; in a way, it is a way to see the bigger picture. Though, paradoxically, this “bigger picture” exists in knowing the nuance of the smaller pieces that make up that picture. Maybe “smaller picture” is better vocabulary.

Naturally, this idea also plays out in the necessity of care and the respect for labor that goes into land restoration, a manifestation of the human-land (or terrapersonal as my dear friend Ruth puts it) relationality. This, too, is something that the good folks of Test Plot uniquely practice.

ON ANOTHER PRACTICAL NOTE....

I unexpectedly became familiar with web design, (a tiny bit of) coding, marketing, social media, volunteer management, spreadsheets, procreate animation, and laser cutting. Being in such a tiny company was incredible, as it afforded me a ton of unexpected problem-solving opportunities. Did I know how to do everything that Jen asked me to do? No! Did I eventually figure them out though? Most of the time, yes! This proved to be rather empowering; while I may not have known exactly how to accomplish some tasks, I felt increasingly confident in my ability to problem solve my way through them. I am certain that, even later in my career, I will never know how to do everything; for that reason, I am extremely grateful to have had the opportunity to leverage my inexperience as a way to learn and to grow in confidence.

ACADEMIC APPLICATIONS....

Working here was the first time I had really come to understand what a seed bank entails. The concept was fascinating enough to inspire a term research project comparing passive revegetation strategies using native seed banks and active revegetation strategies using calculated seed mixes.

The internship also sparked a newfound interest in ethnobotany (which is good, because I spent good, quality time with the La Esquinita tags) Our Fall studio project was located on Chumash land in Santa Ynez, and, after speaking with some tribal members at the local museum, I decided to explore ethnobotany as it relates to the Chumash culture. My proposal of an ethnobotanical “mother plant” garden responded to the joint tribal desires to revitalize pathways of TEK transmission and restore ecological integrity. That idea would not have been possible without having first learned how Tongva and Kizh peoples understood their community’s kinship with their environment.

As I embark on my senior thesis project, (eek, scary!) I am more influenced by the Test Plot framework than ever, particularly as it relates to the social dimensions of land care. My time at Test Plot made it clear to me that I want to work closely with local organizations + nonprofits + charities. I absolutely adored the social aspect of my work, and I found so much joy and purpose in attending events and workdays where people can come together for a purpose larger than the individual. Going forward, I want to continue practicing “human care through land care,” building upon it to include themes of interpersonal relationships and social + environmental justice.

TO CLOSE...

I want to express my gratitude for the entire Test Plot family. From graciously moving my first interview while I was in Nepal to not be at 2am, to letting me hold onto the internship for three months longer than agreed upon, and every micro-lesson in between, they have truly been a blessing. I am exceptionally thankful for the last five months, for every lesson and wise bit of knowledge that Jen has gifted to me, and for the groundedness + care which I look forward to taking into my career. Thank you Test Plot, I love ya!

STORMWATER WORKSHOP #1

Rainbow Canyon Test Plot

DATE: December 07 2025

An Oral History by USC Students in Arch546

“This event felt genuinely healing and grounding for me. The mix of tired muscles, dirt on our hands from pulling weeds, and easy conversations with people who’d been strangers a few minutes earlier made being outside feel quietly joyful in a way I didn’t expect. It was really lovely to see Rainbow Canyon so alive. I also got to put my architecture school education to use by building a birdhouse with friends. It took all three of us, which felt both grounding and humbling, and I really hope the birds end up loving its slightly crooked, handmade charm.”

“Presenting our check dam proposal at the Test Plot community event on Sunday was one of the highlights of my semester. After weeks of finals and studio deadlines, it felt refreshing to step outside the classroom and talk with people who actually live near Rainbow Canyon. I enjoyed explaining our ideas and hearing how residents experience flooding, erosion, and changes in the landscape firsthand. Their reactions were thoughtful and encouraging, and it was exciting to see that people were genuinely interested in how design could improve the canyon. The experience reminded me why architecture and landscape design matter beyond drawings and models̶they can become part of real conversations and real places. It was also a nice break from academic pressure to engage with the community in a relaxed, open setting and see our work spark curiosity and discussion.”

“What a long and fruitful day. I had such a great experience not only being able to see our map sign-in board with the diversity of visitors from areas around LA, SoCal, and internationally, but to get my hands dirty and meet new people. The best moments were when I’d see an untouched pile of dirt and a plant besides it, signifying it needed to be planted. Someone else would be planting nearby, and I asked how they heard about the event. I learned about people who were friends with my classmates, people who attended last December’s workshop and kept up to date with the Testplot instagram, and people who came because their friend lived in the neighborhood and also came to volunteer. These were just beginnings of conversations until I got to meet two costume designers who appreciated spending time with people passionate about the outdoors and a recent grad in the California Climate Action Corps. The event was an opportunity to connect with people over a shared process of planting. For fun, if the day was named after a Spotify playlist, it’d be Beaming Grind Community Sunday Afternoon.”

“During the activities, the flood simulation felt really meaningful, and the mapping exercise was just as important. Marking where everyone came from helped me see how different perspectives shape the way we understand the site. Over the semester I watched Rainbow Canyon slowly grow from barren land into an ecosystem. and it added another layer of meaning to the work we did throughout the day. The tree-planting activity was also memorable—especially having to wrap the plant bases with netting to keep the roots from getting damaged. Building the birdhouses was probably the most fun, and it helped me understand structure in a very hands-on way. And since I worked in digital modeling and integrating information, seeing water move through the physical model made me realize how valuable real, tactile experience is for understanding flood patterns and the site itself.”

“I loved expanding the existing plots with new plants. We’ve been learning what’s growing well and what hs taken longer to etablish. We currently have 7 mini plots that focus on different microclimates and purposes: Two fire buffer plots alongside the homes that border the lower plots contain evergreen species and species that have a low leaf burn rate (see Las Pilitas for data), a riparian plot, two walnut woodland understory plots and two hillside plots that will stabilize the steep access point that connects to Ave 44. In total we planted over 240 native plants donated from Community Nature Connection and Chaminaude Nursery. I’m particularly excited to see how the Canyon Sunflower (Venegasia carpoides) does in the woodland plots as it seems like it should be right at home in this shady, protected canyon. It will add much needed color and brightness.”

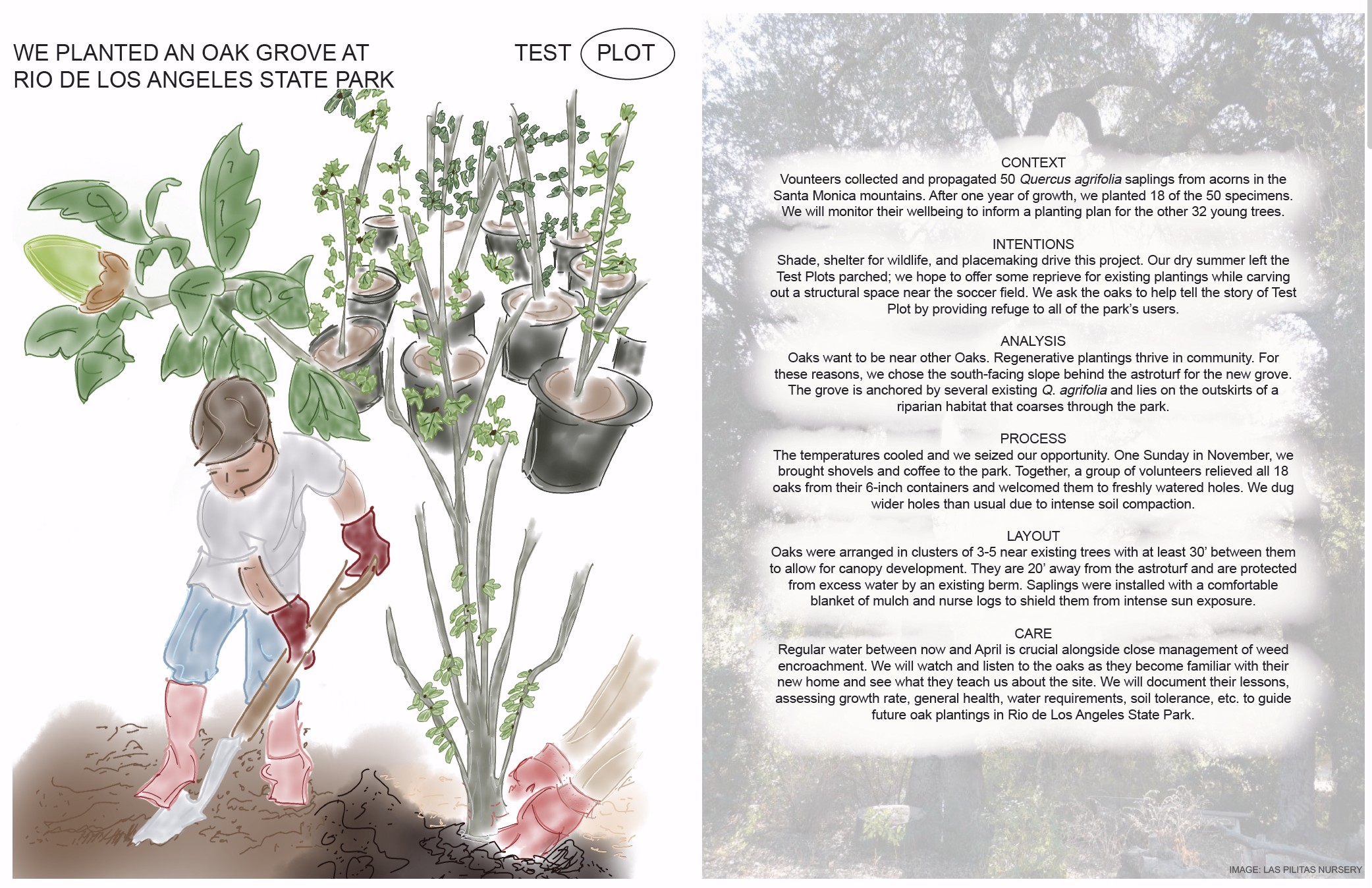

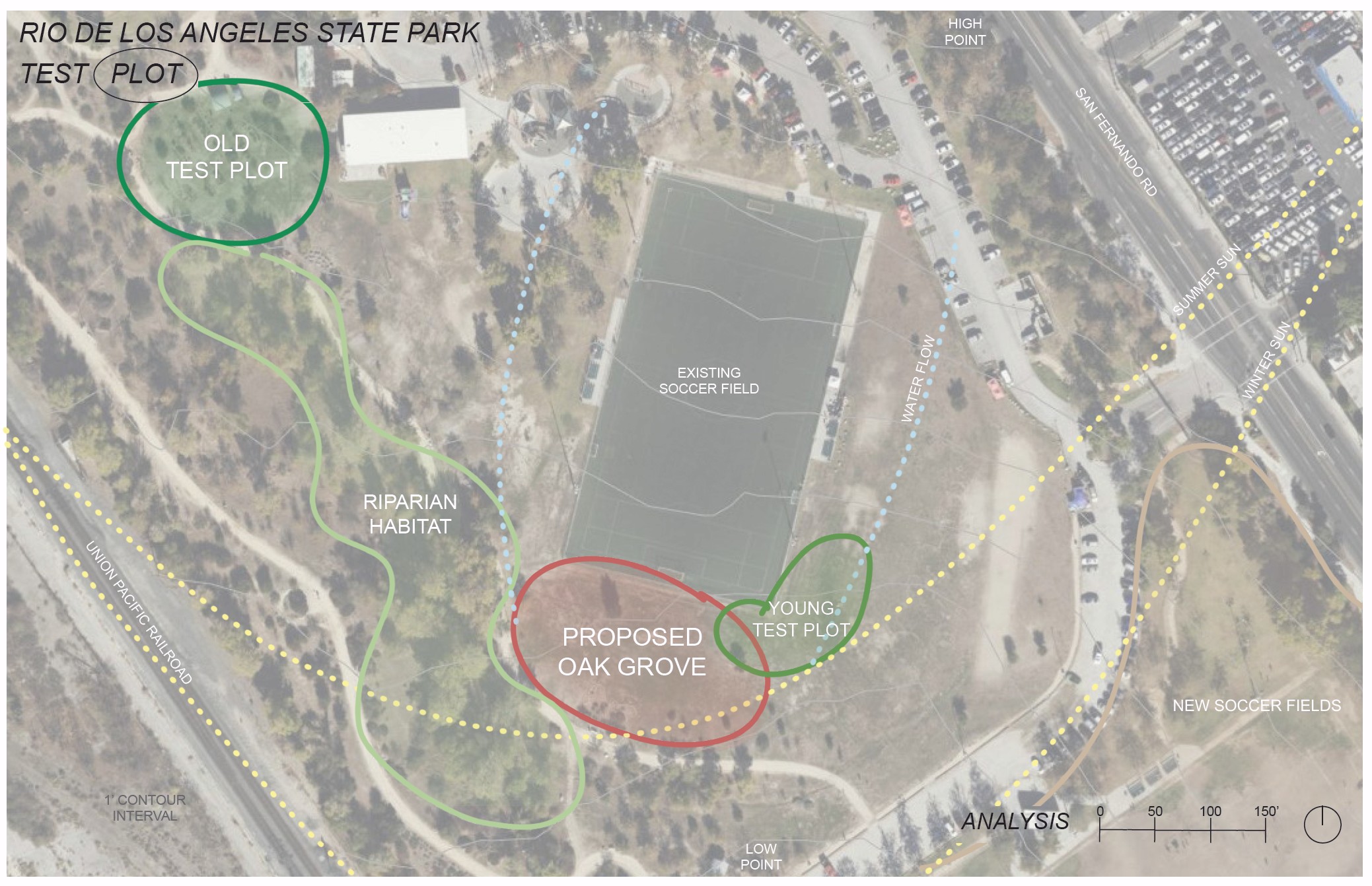

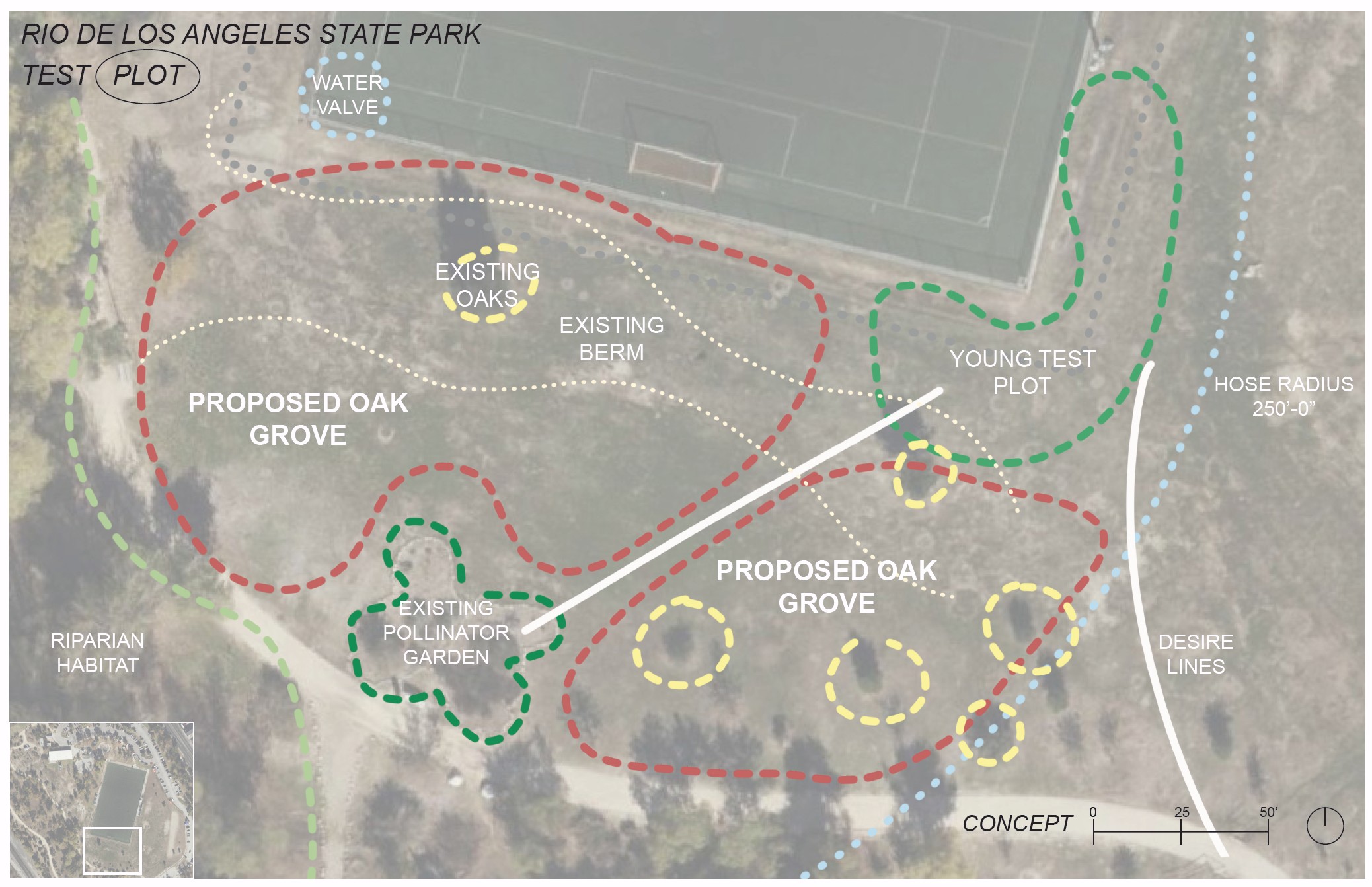

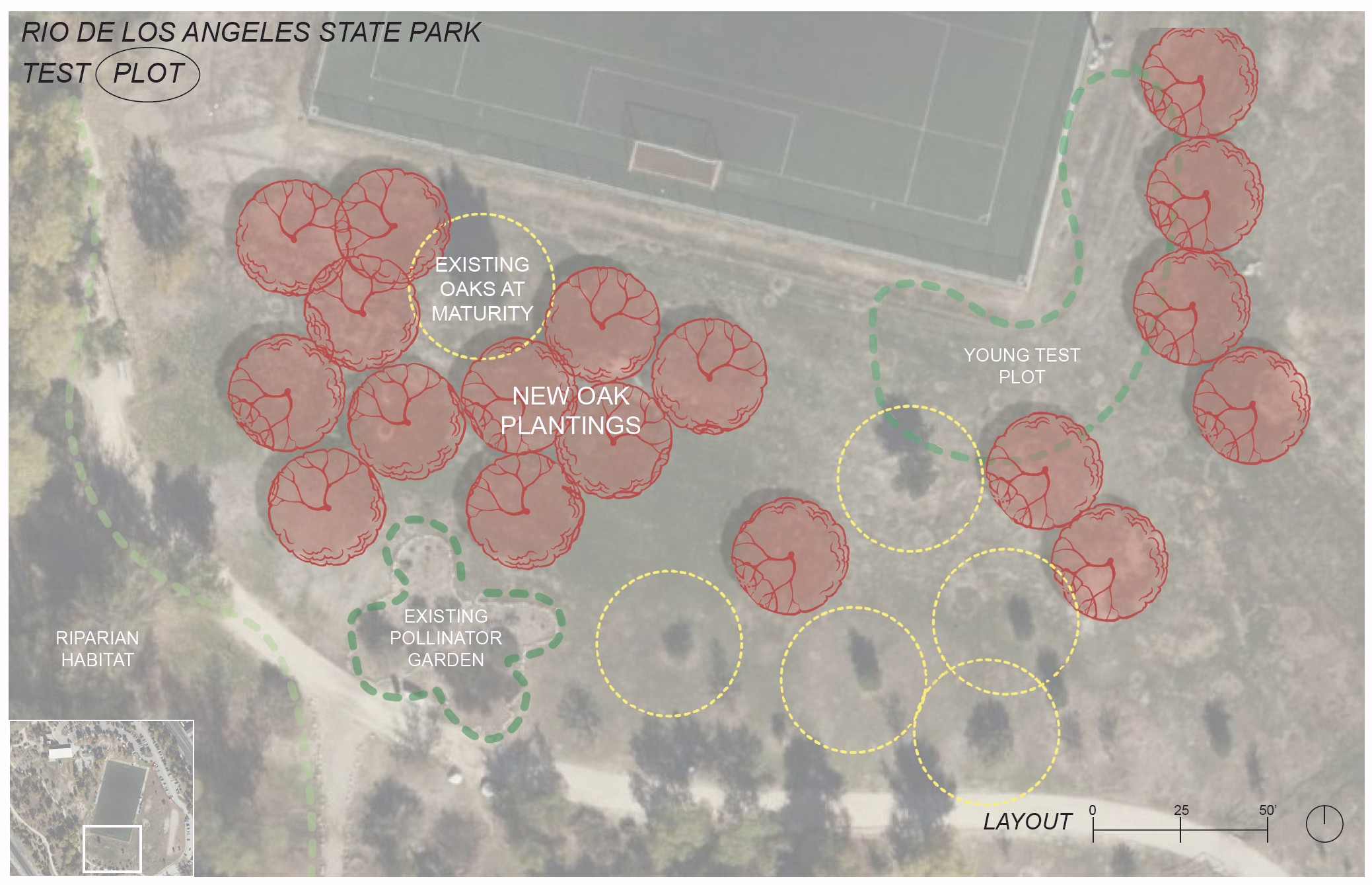

PLANTING AN OAK GROVE

Rio de Los Angeles Test Plot

By Tom Hurst

DATE: Nov 09 2025

SITE SENSORY EVENT, AN ORAL HISTORY

Rainbow Canyon Test Plot

DATE: October 04 2025

During the process of introducing students to the canyon I led them on a few site sensory exercises. These ranged from basic meditation, that we call “Look and Listen”, to measuring exercises, like soil analysis. These were fun, relaxing, and enlightening, so we decided we should share these with the community. In the end, the students conceived of, and prepared, twelve site sensory exercises. These were enacted on Saturday morning on October 4th, 2025 with a great group of volunteers, including a contingent of high school students brought by Community Nature Connection. In the morning, before everything started, a local young birder from the neighborhood, Surya, led a well attended birdwatching walk. The day was sweet and beautiful. Everyone was a bit surprised how much they enjoyed it. After spending most days working in the canyon, it was a treat to spend time just tuning into the place.

— Alexander Robinson

I did a 2:30 hour bird walk through the canyon while practicing deep listening through birding. One thing I noticed was around the end people were more quiet and we found more birds. This shows how listening and focusing on the environment can help you notice more. I also showed the importance of citizen science by submitting a list of the birds seen to a database.

— Surya Jeevanjee

I helped people discover their cognitive preferences with sun versus shade measuring. I expected people to have a preference towards the heat, but it was largely voted for the shaded area as it gave a more calming sensation. I expected to not be able to form a general analysis of temperature preferences, but I noticed while repeating in other spots, there would be a general shift in how long people would want to stay in a shaded v. sunny spot, which was interesting. People seem to prefer a counter temperature to an environment they were raised in (So-Cal heat).

— Alejandro Vasquez

We practiced embracing imperfection and letting go by making art from dried plants, then intentionally destroying it afterward. I went in expecting most participants to make simple circles or grids with the dried plants they collected. Instead, they gravitated toward sculptural pieces shaped by intuition and background. The architects worked systematically: they started at the center, built a boundary, then stacked, and ended up with something like a primitive hut. The kids were bolder and more instinctive, hauling big logs and leaning them together to “build” what they pictured: a large house or a bridge. High school and college students were playful but liked to test the rules, mostly gathering leaves in different colors and arranging the patterns suggested by the reference images. It was also funny watching kids haul logs taller than they were. Lynden grabbed two huge logs and decided each one, on its own, was his artwork. Watching how personal experience steered each approach, and how many different outcomes emerged, was the best part.

— Anh Bui

The event we have is exactly what I was expecting, it was fun, engaging and it’s nice to see how much attention this site receives from its surrounding community. We met Lynden, an interesting 9th grader from a neighboring high school, he sure have a lot of opinions on things and often be the funniest one in our group.

— Jianjun Xu

The sensory activity was a guided blindfolded walk where participants used hearing, smell, touch, and sight to experience the site. I expected the plan was to have them walk through the site four times, each time focusing on one sense, but after the first group, I found it worked better when they stayed in front of the same object and used each sense on the same project. What interested me most was how different relationships changed the experience. Couples and parents with kids moved smoothly. Friends, on the other hand, kept bumping into things, but they were laughing the whole time and having fun. Everyone said they really enjoyed the activity also for me. At first, it felt strange to only rely on other senses, but once I got used to it, it became really fun. We all felt that everything around us seemed closer and more alive than usual.

— Jianye Wang

The Collaborative Atmosphere Collage slowly came to life as people walked through Rainbow Canyon, pausing to sketch places that felt meaningful to them. Each drawing was added to a line stretched between trees, turning into a quiet collection of impressions shared across the site. When sunlight came through the canyon and touched the papers, it felt like the drawings became part of the landscape. That moment — when everyone stood together, looking at what had been created, with the sketches moving gently in the wind — felt like a small exhibition, briefly held in the land itself.

— Jiya Yuan

I helped people create a contour and flow mapping of the test plot. During my activity, the participants were engaged to a surprising extent. They worked fairly hard to map out the creek's contours, too, which I didn't expect to happen and once I explained things to the participants, they were autonomous. I believe the activity thrives in its simplicity and the immediate tactile and visual feedback it produces. I could see participants holding discussion as they methodically worked sideways through the canyon.

— Josiah Hickman

Stream study was conducted where different participants helped measure depth and width at 3 different points in one area, proceeded by the following group conducting the same activity 10 ft away from the previous spot. Following the measurement participants also gave notes on anything they noticed. One observation that was interesting was the amount of litter that is imbedded into the stream, from bottles to shoe inserts. There was also evidence of asphalt which had some participants questioning if there used to be a road in that segment or if it was runoff from rainfall. Participants had fun and were very invested in the exercise. The exercise felt like it was more efficient and enjoyable when people worked in pairs rather than alone. The best part was seeing how people found out about the event through so many different channels and seeing people from different backgrounds come together for this activity.

— Navid Rodd

My main site sensory activity was tree hugging, while the secondary one was the feedback tree. I was a bit nervous going into the event because I wasn’t sure if people would be highly engaged. There were some kinks in the activity when Richard & I tested it the second time we visited Rainbow Canyon, and then we tested it again and had more edits. I was thankful we were able to work together. We had a high school freshman participate, and his personality and engagement were so fun! I considered Richard and I splitting off to run the exercise with different people separately, but we decided to stay together in groups of three. This enhanced the tree-hugging experience because three people hugged one tree at the same time; as they experienced the comfort (or discomfort) from hugging the tree, there was a greater community aspect in doing it together. I laughed a lot, and it was interesting seeing which tree each person chose at the end that they identified with the most comfort with a circle of red string.

— Sara Eyassu

I instructed people on how to complete 15-minute "look and listen" sessions lying down. Many told me that they felt relaxed and took notice of how quiet the canyon was. One thing that surprised me was how many people said that the contours of the canyon felt good for their back pain. A land stewardess shared that she spends so much time taking care of the land, she never stopped to consider how the land could take care of her.

— Zoelli Ortiz

I ran a soil analysis station at saturday’s workshop, in which i encouraged guests to conduct both pH and qualitative texture tests. most participants were surprised to learn that the soil pH was consistent across the site, despite variation in soil sample colors, textures, or locations!

— Haleluya Wondwosen

I worked with Hal. More people joined the soil activity because it was simple and fun to test the soil. The litter mapping started slowly, but after some time, people joined in. The kids were more interested in storytelling and discovery than in cleanup. They preferred to talk and act things out rather than write. I had to ask them again and again to try. One kid named Unni found an old tyre laying around and started making up stories about it. The children liked talking and telling stories more than writing or picking up trash. The adults, on the other hand, were more comfortable participating in both mapping and writing. They engaged once they understood the purpose of the activity. Overall, the litter mapping exercise worked, but it needs to be simpler and more fun — maybe more talking or drawing instead of writing.

— Sai Ravikumar

Walking through the canyon blindfolded meant I had to completely trust Sarah. She guided my hand up towards things to touch and handed me things to smell. I became aware of the gentle slope of the canyon floor, noting I had to pick up my feet more! I liked how the small groups of people chatting became anchors that helped me orient myself. Despite being blindfolded, it felt carefree, like a return to childhood.

— Jen Toy